Designing Hotels for the People’s Republic of China (Part II)

By WATG

December 17, 2015

As part of our 70th Anniversary celebration, we’ll be revisiting past articles and interviews of our founders and past employees of WATG. The following is part 2 of an article written by Greg Tong published in the May 1979 issue of The Cornell H.R.A. Quarterly. Greg shares his experience of being the first Western architect to do work in the People’s Republic of China (before diplomatic relations were established). The Huashan and Kweilin hotels were never built.

Click here for part 1.

Paving the Way for Future Construction

In working on the Huashan project, we were keenly aware of our responsibility to derive an elegant architectural solution that would set high standards for future buildings of a similar nature. Furthermore, as one of the first major highrises, the Huashan will be used not only as a model for later projects but also as a thorough teaching laboratory in design, construction, and operation for contractors, technicians, and other workers from throughout the People’s Republic.

Avoiding urban sprawl was one of our main objectives in developing design plans for the Huashan Hotel’s physical structure. Shanghai is the world’s most populous city, but the Chinese were reluctant to release the productive agricultural land surrounding Shanghai for new construction; they preferred the notion of high-density construction in the inner city.

The present skyline of central Shanghai is 18 to 20 stories high, and we first considered maintaining this height for the Huashan. Because of the required capacity, however, this plan would have resulted in a massive, squat building. The Chinese accepted instead our plans for a slender, 38-story property.

The Huashan Hotel will be one of the first modern highrises in China.

The Huashan Hotel will be one of the first modern highrises in China. The Chinese are technically capable of building highrises but the shortage of modern construction equipment has deterred them from constructing buildings taller than 24 stories . Heavy construction equipment, climbing cranes, pile drivers, and concrete pumps will all be imported for the project, as will cement and reinforcing steel (the Chinese manufacture these two products but not in sufficient quantity to meet the needs of the nation’s current construction program). Glass is also limited in quality and size; as far as we have been able to determine, the largest pane available is about three feet by six feet.

Harmony and Horticulture

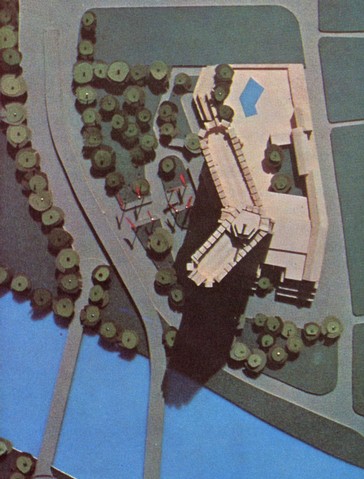

The Chinese city planners are particularly sensitive to the problem of maintaining harmony with existing buildings. We believe that the proposed design for the Huashan Hotel will serve as an example for future Shanghai construction, demonstrating how to make a thoughtful transition from the existing to the new. While most of the existing structures are short and broad, the Huashan has a broad base and grows narrower at the top. This design lends stability to the building–an important consideration in an earthquake zone–and relates well to the shape of other buildings, creating a graceful silhouette. Also contributing to a sense of Chinese architectural style, however subtly, is the gentle sweep of the parapet, reminiscent of traditional Chinese rooftops. Shanghai has a distinctive ambience, and although we are pleased to be involved in a project that will contribute to the city’s modernization, we tried in our design to preserve the unique character of the area.

Although Shanghai’s planners have chosen to accept high-density construction in the inner city, the love of open spaces and gardens is still very strong among the Chinese. Plants abound in even the most crowded streets of the most metropolitan cities. In Shanghai, the main thoroughfares are not very wide (perhaps six lanes at their widest) and thus are quite crowded, yet they are lined with trees even in the heart of the city. To reflect this emphasis on nature, 60 percent of the Huashan site will be left open for landscaping, with the remaining 40 percent allocated to building coverage. The “back of the house” roof deck will also be landscaped. This is an especially generous amount of landscaping for an urban hotel–and it was the planners’ emphasis on open space and gardens, more than any other factor, that dictated the height and shape of the Huashan’s design.

Although we were called upon to incorporate many unusual features in our design of the Huashan Hotel, these peculiar design requirements did not pose any serious problem because the Chinese planners’ needs were communicated to us at a preliminary stage. Sometimes confused by a particular request, we would ask why that component was necessary–and once we understood the logic we were often able to suggest alternative approaches (for example, that they import a piece of equipment unavailable or unknown in China).

Under the present Chinese system of central government, it is relatively simple to accelerate the construction of a project if the project is considered sufficiently important. For example, if the Shanghai hotel is deemed of high priority in relation to national goals, the assigned construction team can request that skilled technicians and laborers from throughout the country be brought in to work on the project (perhaps directly from a project of lower priority). In other words, the team can bring in 200 electricians simply by asking, if it deems it advisable to do so. The priority system applies not only to the nation’s labor pool but also to the supply of raw materials for construction. As a result, China can complete a priority project in record time, even without sophisticated building equipment, just by applying sheer numbers of workers to the project.

The Inscrutable West

From our point of view, the most demanding aspect of this undertaking was probably not our unfamiliarity with Chinese design requirements and technology but the need for secrecy during our earliest negotiations. It is a company policy to maintain complete confidentiality regarding any project under negotiation, but the need for circumspection was especially critical in this case because we entered into negotiations before the United States established diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic.

Obviously, any word that our firm was negotiating with the Chinese would have received a great deal of news coverage, which could conceivably have brought the project to a halt.

Obviously, any word that our firm was negotiating with the Chinese would have received a great deal of news coverage, which could conceivably have brought the project to a halt. Only the firm’s partners knew of the negotiations. Even our secretaries, who typed all of the correspondence pertaining to the projects, were kept in the dark; we referred only to “Project A” (the Huashan Hotel) and “Project B” (the Kweilin resort) in our letters. We booked flights into Hong Kong–because our firm is active in the Hong Kong area, this raised no suspicions–and our contact there arranged for our travel into China.

A Passage to China

Our negotiations with the Chinese began only in September of last year, but it was almost a decade ago that we made a formal corporate decision to try entering the Chinese market (because it seemed clear that the U.S. would establish normal trade relations with China before long, and because one simply can’t ignore a nation with a fourth of the world’s population).

After attempts to establish contact through American and Canadian agencies failed, we worked through interests in Hong Kong, which had established trade relations with China. Robert Kuok, a Hong Kong entrepreneur we had worked with before, arranged the meetings with Chinese officials that culminated in our undertaking of the projects. The two planned hotels represent a joint venture of the China Travel Service–a tourism-development and construction agency–and Kuok Travel Service.

As part of its tourism-expansion program, China plans to develop hotels in major cities and scenic resort destinations throughout the country- and it is looking to the United States for much of the outside expertise needed to implement the program. From the Huashan project the Chinese will learn modern design and construction techniques. And we expect to learn a great deal from the Chinese about their construction methods, particularly as they relate to cultural design elements. We hope to incorporate local ethnic touches wherever possible in the Huashan (in recreation areas, for example, or a specialty dining room). It is our intent not to create a contemporary highrise hotel that looks like a Chinese pagoda, but rather to design a hotel whose exterior has international appeal, with cultural elements reflected in the interior design.

We were favorably impressed with both the technical ability and the receptive attitude of the Chinese: they are ready to accept the most modern concepts in design and construction. They are also quick to grasp both the direct and intangible implications of proposed design solutions and to assess the relative merits of hypothetical situations. China’s modernization is likely to take the form of planned, controlled growth, rather than the haphazard, piecemeal development common to many emerging nations; in making decisions, Chinese planners give priority to long-term rather than short-term considerations and emphasize, in Western vernacular, “the big picture.”

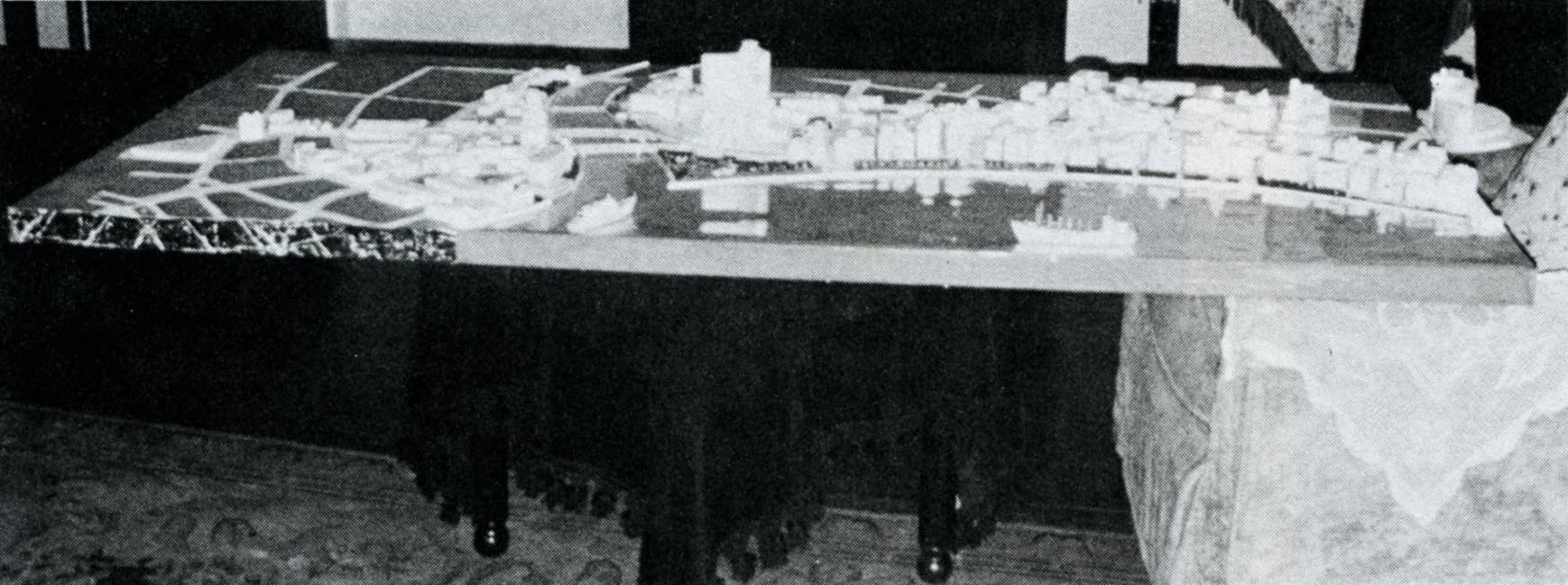

The planners used a model of downtown Shanghai, pictured above, to determine how each proposed design would affect and be affected by the rest of the cityscape. They also photographed the site from various distances and an artist sketched in the proposed hotels to determine how each would complement the city’s skyline.

After we had completed our presentations and proposals, the Chinese met alone for one day of discussions and gave us the go-ahead on the next day.

Communication was sometimes problematic.

Communication was sometimes problematic. Imprecise translation of correspondence made it difficult to divine what the Chinese wanted and needed in the way of design. For example, we initially thought they had asked us to design buildings similar to existing structures-and discovered only when we met face to face, with sketches in hand, that they were interested simply in achieving a certain degree of harmony between the old and the new. Although we were assisted by very capable translators during the negotiations, many of the words we used–especially technical terms–have no equivalent in Mandarin.

A Final Note

The two approved hotel projects represent a major step forward for both the United States and China. One Chinese official informed our firm that China is pleased and eager to enlist our aid in designing hotels. We in turn are pleased and eager to play a part in the opening up of the Middle Kingdom and the cultivation of economic and human relations between our two nations.

Latest Insights

Perspectives, trends, news.

- News |

- Trends

Interior Design Trends 2025: Emotional, Experiential, and Environmentally Conscious Spaces

- News |

- Trends

Interior Design Trends 2025: Emotional, Experiential, and Environmentally Conscious Spaces

- Strategy & Research |

- Trends

2025 Outlook: WATG Advisory predicts the top hospitality trends.

- Strategy & Research |

- Trends

2025 Outlook: WATG Advisory predicts the top hospitality trends.

- Employee Feature

Unlocking Value & Vision: Guy Cooke & Rob Sykes Discuss WATG Advisory’s Bespoke Approach

- Employee Feature

Unlocking Value & Vision: Guy Cooke & Rob Sykes Discuss WATG Advisory’s Bespoke Approach

- Case Study |

- Design Thinking & Innovation

In Conversation: Marcel Damen, General Manager of Rissai Valley, a Ritz-Carlton Reserve

- Case Study |

- Design Thinking & Innovation